Video Courses

Video Courses Video Courses

Video CoursesThe structure of this article is based on a lecture I attended at the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland a number of years ago. The talk, delivered by Infectious Diseases Specialist, Dr David Gallagher (Galway University Hospital), was memorable and his approach to this topic has helped me greatly in practice.

Disclaimer: This is a ‘pop’ article. The article is not endorsed by any clinical body. The author does not have a passport and, perhaps wisely, never journeys ‘beyond the Pale’ (Dublin and North East Wicklow).

Increasingly, we are required to deal with people returning from the tropics with fever. Such cases cause generalists considerable anxiety as we worry about our limited knowledge of the differential. In fact, the differential in the acute setting is itself quite limited. In this situation, three common infections should be foremost in our minds, Malaria, Dengue and the wonderfully named Chickungunya.

The possibility of malaria must be considered in any febrile individual returning from a malaria endemic area. It is the tropical infection most likely to kill if not picked up early and treated appropriately. The classical manifestations described in textbooks (cyclical chills and fevers) are not generally relevant to the returning traveller. A ‘flu like illness’ often with gastrointestinal upset is typical in this group. As the presentation is non-specific, the key to avoiding missing the diagnosis is a high index of suspicion and knowledge of the limitations of available laboratory tests.

Alexander the Great with his physician, Philip of Acarnania. It has been postulated that at the age of 32 years, having conquered the known world and survived at least one previous tropical disease, Alexander died of malaria in Babylon in 323 BC.

“The sensitivity and specificity of all RDTs is such that they can replace or extend the access of diagnostic services for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria…..If the point estimates for Type 1 and Type 4 tests are applied to a hypothetical cohort of 1000 patients where 30% of those presenting with symptoms have P. falciparum, Type 1 tests will miss 16 cases, and Type 4 tests will miss 26 cases. The number of people wrongly diagnosed with P. falciparum would be 34 with Type 1 tests, and nine with Type 4 tests.” Abba et al, Cochrane review 2011.

Source: Hahn WO and Pottinger PS. Med Clin North Am 2016 100(2): 289

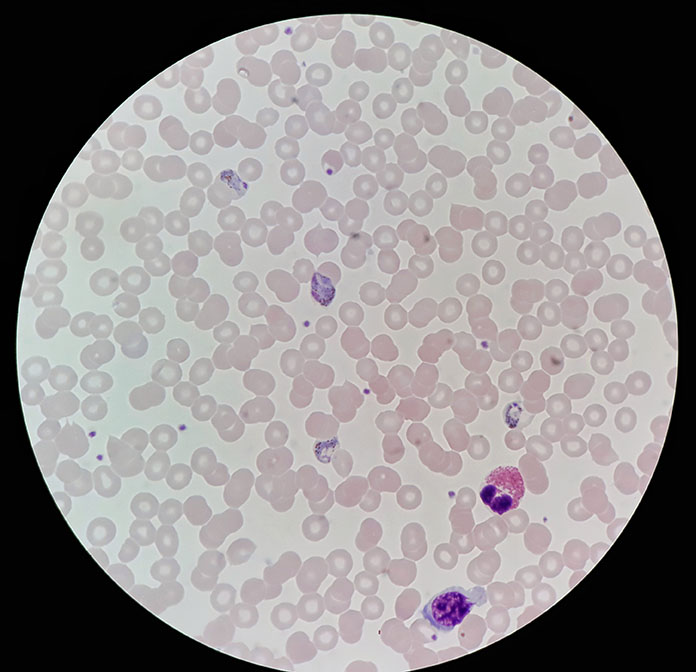

Malaria parasites detected on a thick blood film

This flavivirus infection produces a spectrum of illness severity ranging from asymptomatic infection to the potentially lethal clinical syndromes, Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever (DHF) and Dengue Shock Syndrome (DSS). Presentation is nonspecific and again a high index of suspicion in subjects returning from endemic areas is required in order to avoid missing this diagnosis.

Dengue fever. The characteristic macular arch develops in over 50% of infected individuals.

Laboratory tests, RTPCR, viral isolation and serology can establish the diagnosis of dengue virus in the body. The interpretation of these tests is complicated and beyond the scope of this article. There is no specific treatment for dengue and the key to appropriate management is that we look for ‘warning signs’ pointing towards the potential development of DHF and DSS. A patient manifesting these ‘warning signs’ should be admitted with close observation and supportive measures instigated as necessary.

“Warning signs” in Dengue infection suggestive of progression to potentially lethal complications

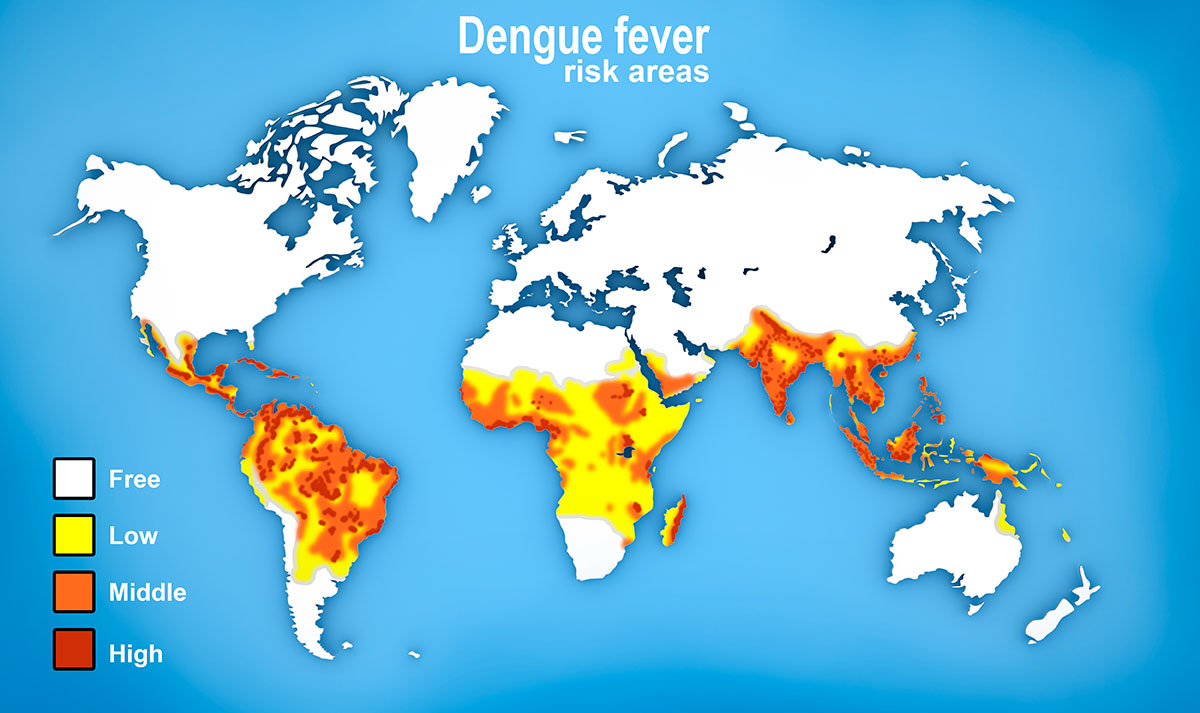

The global risk of dengue infection

‘The illness of the bended walker”

This infection, originally described on the border of Tanzania and Mozambique derives its name from the local Makonde language. The name (“that which bends up”) refers to the contorted nature of those afflicted by the infection due to the associated joint problems. The disease is prevalent throughout the developing world.

‘Behind you’! An intrepid traveller takes a break from searching for gorillas (arrow) on a recent trip to Africa

The presentation is nonspecific but as the name implies may include joint problems. Diagnosis is confirmed by serologic methods, virus isolation (if available), and reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR). There is no specific treatment.

The time between exposure to the infectious agents discussed here and the onset of symptoms (the incubation period) is important in deciding on a likely diagnosis or in excluding an unlikely diagnosis.

Dengue* 3 days (2 -10)

Chickungunye* 4 days (3 -10)

P. falciparum^ 7 to 14 days

^Incubation period may be prolonged by partially effective prophylaxis. P. ovale and P. vivax may manifest an incubation period of up to several years.

*Sources: Rudolph et al. Am J Trop Med Hyg 90(5): 882-891 2014, Bartoloni and Zammarchi. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2012 4(1) e2012026

Typhoid: incubation period of one to two weeks. Presents with fever, headaches and abdominal pain. Diarrhoea may be a feature. Diagnosis ideally confirmed on culture of Salmonella typhi from body fluids supported by tests for relevant pathogen antigen or DNA in blood samples.

Hepatitis: check the LFTs and serology

Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD)

Taking a full sexual history is an essential part of the workup of an individual returning from abroad with a fever.

…and don’t neglect ‘home-town’ infections

A person may return from the tropics and pick up a ‘local’ infection. For example, it would be a disaster to miss a case of bacterial meningitis presenting with headache and fever when focused on the possibility of P. falciparum infection in a returned traveller! As always, if you have time to think, keep an open mind.

It is worth being aware that tropical diseases themselves may be on the move. We might not think of Chickungunya or Dengue as being relevant to travel in Europe or the United States but they are and may become an increasingly prevalent problem in the near future. The CDC website carries useful up to date information on the distribution of tropical diseases around the world and is well worth consulting when in doubt.

Source: The Lancet Infectious Diseases. Editorial. Volume 14(10) 899 2014

It is remarkable that we got through this article without a photograph of or indeed mention of a mosquito. Doh!

DisclaimerPrivacy PolicyTerms of UseData Deletion© Acadoodle 2025